Constipation is an important problem in the

pediatric emergency department for many reasons. It is one of the most common

pediatric complaints, accounting for 3% of primary care visits. There are many

causes for constipation (Table 13.1), some rare and some very common (Table

13.2). Occasionally, the presentation of constipation is atypical, with chief

complaints that superficially seem unrelated to the gastrointestinal tract

(Table 13.3). Although relatively rare, some causes of constipation are

potentially life threatening and need to be recognized promptly by the

emergency physician (Table 13.4). In addition, constipation may produce

symptoms that mimic other serious illnesses such as appendicitis.

DEFINITION

Although constipation most commonly is defined

as decreased stool frequency, there is not one simple definition. The stooling

pattern of children changes based on age, diet, and other factors. Average

stooling frequency in infants is approximately 4 stools per day during the first

week of life, decreasing to 1.7 stools per day by 2 years of age, and

approaching the adult frequency of 1.2 stools per day by 4 years of age.

Nevertheless, normal infants can range from 7 stools per day to 1 stool per

week. Older children can defecate every 2 to 3 days and be normal.

It is easier to define constipation as a problem

with defecation. This may encompass infrequent stooling, passage of large and/or

hard stools associated with pain, incomplete evacuation of rectal contents,

involuntary soiling (encopresis), or inability to pass stool at all.

PHYSIOLOGY

The passage of food from mouth to anus is a

complex process. The intestine relies on input from intrinsic nerves, extrinsic

nerves, and hormones to function properly. Normal defecation involves voluntary

and involuntary components. Disruption of any of these can result in

constipation. The colon is specialized to transport fecal material and balance

water and electrolytes contained in the feces. When all is functioning well,

the fecal bolus arrives in the rectum formed but soft enough for easy passage

through the anus. Normal defecation requires the coordination of the autonomic

and somatic nervous systems and normal anatomy of the anorectal region. The

internal anal sphincter is a smooth muscle, which is innervated by the

autonomic nervous system. It is tonically contracted at baseline. It relaxes in

response to the arrival of a fecal bolus in the rectum, allowing stool to descend

to the portion of the anus innervated by somatic nerves. At this point, the

external anal sphincter, striated muscle under voluntary control, tightens

until the appropriate time for fecal passage. Before defecation, squatting

straightens the angle between the rectum and the anal canal, allowing easier

passage. Voluntary relaxation of the external anal sphincter allows passage of

the feces, and increasing intraabdominal pressure via Valsalva aids the

process.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

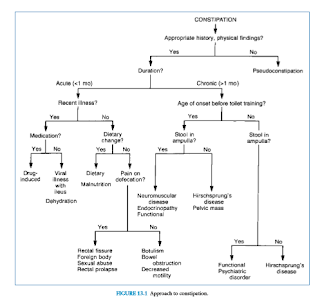

The evaluation of the child presumed to have

constipation should begin with a thorough history and physical examination.

Special attention should be paid to the age of the patient, duration of

symptoms, timing of first meconium passage after birth, changes in frequency and

consistency of stool, stool incontinence, pain with defecation, rectal

bleeding, presence of abdominal distention and/or palpable feces, and a rectal

exam to assess anal position, sphincter tone, widening of the rectal vault, and

presence of hard stool. A complaint of constipation is not sufficient for

diagnosis. A decrease in stool frequency or the appearance of straining is

often interpreted as constipation. The physician should be aware of the

grunting baby syndrome, or infant dyschezia, in which an infant grunts, turns

red, strains, and may cry while passing a soft stool. This is the result of

poor coordination between Valsalva and relaxation of the voluntary sphincter

muscles. Examination reveals the absence of palpable stool in the rectum or

abdomen. Complaints of constipation not supported by history or physical

examination are called pseudoconstipation (Fig. 13.1).

Acute Constipation

Constipation is not a disease; it is a symptom

of a problem. Constipation is acute when it has occurred for less than 1

month’s duration. The patient’s age and the duration of the constipation are

important when determining the cause and significance of the problem.

The infant younger than 1 year of age with true

constipation is particularly concerning. Potential causes include serious

diseases such as dehydration, malnutrition, and infant botulism. A recent viral

illness accompanied by dehydration from excessive water loss through vomiting,

diarrhea, fever, and increased respiratory rate can precipitate acute

constipation in an infant. Adynamic ileus or decreased intake after

gastroenteritis may cause slower transit time through the colon, which can also

lead to hard stools. Anal fissures and/or diaper rash after a bout of diarrhea

may precipitate painful defecation, resulting in stool retention. In this case,

the infant may assume a retentive posture consisting of extension of the body

with contraction of the gluteal and anal muscles.

Excessive intake of cow’s milk, inadequate fluid

intake, and malnutrition should all be uncovered by a complete dietary history.

Recent courses of medication cannot be overlooked because many can cause

constipation (Table 13.5). Ingestion of lead is also a potential and serious

reason for constipation.

Infantile botulism commonly presents with acute

constipation, weak cry, poor feeding, and decreasing muscle tone. Acute constipation can also be a symptom of a bowel obstruction, but is

normally a less prominent feature than other symptoms.

Acute constipation in the child older than 1 year of age occurs for many of the same reasons as in the infant. History may reveal recent viral illness or use of medication, as well as the presence of underlying illness, such as neuromuscular disease. Physical examination suffices to rule out anal malformations and other physical problems that could result in trouble defecating.

Chronic Constipation

Constipation of more than 1 month’s duration in

an infant, although probably a functional problem, is especially concerning and

should prompt consideration of an underlying illness. Spinal muscular atrophy,

amyotonia, congenital absence of abdominal muscles, dystonic states, and spinal

dysraphism, which cause problems with defecation, can be readily diagnosed with

history and physical examination.

Anorectal anomalies occur in approximately 1 in

2,500 live births. Anal stenosis causes the passage of ribbonlike stools with

intense effort. Diagnosis is made by anal examination, which demonstrates a

tight, constricted canal. The condition is treated by repeated anal dilations,

sometimes over several months. The anus can be covered by a flap of skin,

leaving only a portion open for passage of stool. This “covered anus” may

require anoplasty with dilation. Anterior displacement of the anus is believed

to cause constipation by creating a pouch at the posterior portion of the

distal rectum that catches the stool and allows only overflow to be expelled

after great straining. The treatment may be medical or surgical.

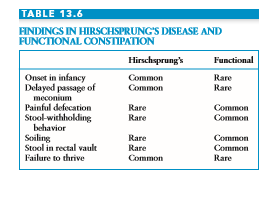

Hirschsprung’s disease, or congenital

intestinal aganglionosis, is rare but must be considered in the constipated

infant because it has the potential to cause life-threatening complications.

The incidence is 1 in 5,000 live births, with a male:female predominance of

4:1. As a result of failure of migration of ganglion cell precursors along the

gastrointestinal tract, there is the absence of ganglion cells in the

submucosal and myenteric plexuses of the affected segment. The absence of

ganglion cells leaves the affected segment tonically contracted, blocking

passage of stool. The segment proximal to the blockage dilates as the buildup

of stool progresses. In most cases, the child never feels the urge to defecate

because the blockage is proximal to the internal sphincter and anal canal.

In Hirschsprung’s disease, abdominal

examination often yields a suprapubic mass of stool that may extend throughout

the abdomen. Rectal examination reveals a constricted anal canal with the

absence of stool in the rectal vault, commonly followed by expulsion of stool

when the finger is removed. The combination of palpable abdominal feces and an

empty rectal vault is abnormal and must be further investigated.

Megacolon in Hirschsprung’s disease can lead to

enterocolitis characterized by abdominal distension; explosive stools, which

are sometimes bloody; and fever progressing to sepsis and hypovolemic shock.

Enterocolitis represents a major cause of mortality in this condition.

Of infants with Hirschsprung’s disease, 80% are

diagnosed within the first year of life. A history of late passage of meconium

is often found (Table 13.6). However, if the involved segment is relatively

short, the diagnosis may be delayed. If suspected, diagnosis is supported by

unprepped barium enema, which typically demonstrates narrow bowel rapidly

expanding to a dilated area. This transition zone represents the location where

the aganglionic, tonically contracted bowel meets the dilated, innervated

bowel. In disease where only a short segment of bowel is involved, barium enema

may miss the transition zone and anal manometry aids in diagnosis. Confirmation

is achieved by demonstration of aganglionosis on biopsy.

Hypothyroidism in the infant may present with

constipation. Water-losing disorders such as diabetes insipidus and renal

tubular acidosis may also contribute to this condition. Cystic fibrosis can

present with constipation alone; when there is a history of delayed passage of

meconium and Hirschsprung’s disease has been ruled out, evaluation by a sweat

test is indicated.

Chronic constipation in the older child is

overwhelmingly likely to be functional constipation. Typically, a cycle of

stoolwithholding starts when the child disregards the signal to defecate and

strikes a retentive posture—rising on the toes and stiffening the legs and

buttocks. This maneuver forces the stool out of the anal canal and back into

the rectum, which subjects the fecal bolus to further absorption of water. The

longer the stool sits, the more likely defecation is to be painful and

traumatic. This reinforces stool-withholding behavior, creating larger and

harder stool in the rectum.

Over time, in functional constipation, the rectum dilates and sensation diminishes. Eventually, the child loses the urge to defecate altogether. Watery stool from higher in the gastrointestinal tract can leak around the large fecal mass, causing involuntary soiling, or encopresis. This may be misconstrued as diarrhea or as regression in the toilet-trained child. Many parents consult a physician at this point. Other reasons parents seek medical attention for their children are abdominal pain, anorexia, vomiting, and irritability.

Peak times for constipation to develop are when

routines change. Toilet training represents a major alteration in the toddler’s

routine. It is also a time when the child and caregiver battle for control.

Another problematic time is after starting school, when a child may be

uncomfortable using an unfamiliar bathroom or unable to adapt to a lack of

privacy. Involvement with friends or games may distract a child from the signal

to defecate. Painful defecation from streptococcal perianal disease or sexual

abuse must be remembered as potential precipitants of stool withholding. In

addition, functional constipation can be associated with dysfunctional urinary

voiding and urinary tract infections.

A history supportive of functional constipation includes retentive posturing, infrequent passage of very large stools, and involuntary soiling during the peak ages. Physical examination typically reveals palpable stool in the abdomen. The back should be inspected for skin changes over the sacral area, which would suggest spinal dysraphism. Normal deep tendon reflexes and strength in the lower extremities in conjunction with a normal anal-wink reflex virtually excludes neurologic impairment. The anus should be normal in placement and appearance. Rectal examination typically yields a dilated vault filled with stool. Abdominal flat-plate x-ray can be helpful but is not necessary (Fig. 13.2). Failure to thrive is not associated with functional constipation and, if present, should prompt further investigation.

Although functional constipation encompasses

most cases of chronic constipation in the child older than 1 year of age, the

less common causes must always be considered.

As in the infant, endocrine abnormalities and

other disorders can cause and present as constipation. Hypothyroidism is often

associated with constipation, as well as with sluggishness, somnolence,

hypothermia, weight gain, and peripheral edema. Diabetes mellitus produces

increased urinary water loss and, in the long term, intestinal dysmotility,

which can lead to constipation. Hyperparathyroidism and hypervitaminosis D,

which lead to increased serum calcium, cause constipation through decreased

peristalsis. Celiac disease is also recognized as a cause of chronic

constipation.

Rarely, an abdominal or pelvic mass may present

with chronic constipation. Careful abdominal examination will demonstrate the

mass. Rectal masses may present similarly. Follow-up again is emphasized

because a mass that does not resolve after clearance of impaction needs further

evaluation. Hydrometrocolpos can present with constipation and urinary

frequency; therefore, a genital examination is indicated in girls to document a

perforated hymen. One must also remember that intrauterine pregnancy is a

common cause of pelvic mass and constipation in adolescent girls.

Children with neuromuscular disorders often

develop chronic constipation. Myasthenia gravis, the muscular dystrophies, and

other dystonic states can predispose children to constipation through a number

of mechanisms. A detailed history and physical examination should recognize

most neuromuscular problems, allowing symptomatic treatment to be provided.

Psychiatric problems must not be forgotten in

the evaluation of constipation. Depression can be associated with constipation

secondary to decreased intake, irregular diet, and decreased activity. Many

psychotropic drugs can cause constipation. Anorexia nervosa may present with

constipation because of decreased intake or metabolic abnormalities, and

laxative abuse can cause paradoxical constipation.

TREATMENT

Simple acute constipation in an infant should

be treated initially with dietary changes (Table 13.7). Decreasing consumption

of cow’s milk, possible formula change, and increasing fluid intake when

appropriate may be enough to alleviate the symptoms. In addition, supplementing

the diet with sorbitol as found in prune, pear, white grape, and apple juice

can be helpful to soften the stool and improve stool passage. If dietary

measures are not sufficient, lactulose or barley malt soup extract (Maltsupex®)

may be useful as osmotic agents. Historically, Karo® corn syrup had been used

as an osmotic agent, but its use has fallen out of favor after concerns that

the syrup may contain spores of Clostridium botulinum. Stool lubricants such as

mineral oil should not be used in children younger than 3 years of age and

should also be avoided in some older children when aspiration is a risk.

Polyethylene glycol solutions such as MiraLax® have gained increased use in the

outpatient setting (see discussion below). When perianal irritation or anal

fissures are present, local perianal care may decrease the risk of painful

defecation, which, in turn, may decrease stool-retentive behavior. Follow-up is

the most important aspect of treating simple constipation.

Therapy for acute functional constipation in

the child older than 1 year of age should be the same as that for the infant,

with dietary changes and stool softeners as mainstays; however, attention

should also be paid to psychological factors such as recent stress that may be

complicating the situation.

Treatment for chronic constipation in the

infant younger than 1 year of age should include ongoing dietary measures

including several daily servings of pureed fruits and vegetables, sorbitol-containing

juices, and possible formula change. If dietary measures alone are insufficient

to control symptoms, a daily stool softener such as lactulose can be used to

help maintain soft stool passage and a glycerin suppository can be used on

occasion to disimpact the rectum, although this should not be used regularly.

Although safety data are still emerging, polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350

(MiraLax®, GlycoLax®) may also be a safe and effective treatment for chronic

constipation in infants. Loening-Baucke and colleagues studied 20 children and

Michail and colleagues studied 12 children younger than 1 year of age, who were

safely and successfully treated with PEG 3350 used for several months or more.

Although more safety data is needed to make specific recommendations, this will

likely become one of the therapeutic options for this age range.

Treatment (Table 13.7) for chronic functional

constipation in the child older than 1 year of age begins with disimpaction and

evacuation of the stool remaining in the colon. This is accomplished with

either oral or rectal therapy or a combination of the two. A study by Youssef

et al. demonstrated that in fecally impacted children whose palpable stool mass

did not extend above the level of the umbilicus, PEG 3350 at a dose of 1 to 1.5 g per kg per day (up to

a maximum of 100 g per day) given for 3 days was an effective method of

disimpaction and evacuation. Other oral options include lactulose, sorbitol,

senna, bisacodyl, PEG electrolyte solution, magnesium hydroxide, and magnesium

citrate. Rectal disimpaction can be accomplished with hypertonic phosphate

(Fleet®) enemas or bisocodyl suppositories. A mineral oil enema administered

the night before the first phosphate enema may soften existing stool, allowing

less painful passage. Phosphate enemas are typically dosed at one adult-sized

enema (133 mL) for patients 3 years and older, and one pediatric-sized enema

(66 mL) for those 1 to 3 years of age. Phosphate enemas should not be used in

children younger than 1 year. The enema may be repeated, spaced 24 hours apart,

with a maximum of three total doses. Subsequent doses should only be given if

evacuation of the previous dose has occurred. Phosphate enemas should be used

with caution in patients with dehydration, prolonged enema retention, or renal

impairment because such use has rarely been associated with severe

hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and tetany, and consequent life-threatening

complications. Tap water and soapsuds enemas should be avoided because of the

possibility of water intoxication. Enemas will disimpact but oral agents are

often needed in addition to produce full bowel evacuation. If there is no

response after 2 days, more aggressive disimpaction under physician supervision

is indicated. Oral phospho-soda preparations

should never be used in children and have been removed from the market

secondary to serious electrolyte abnormalities.

The long-term maintenance phase of therapy,

which is equally as important as the disimpaction and evacuation phase,

involves nonstimulant osmotic laxatives, lubricants, fluids, fiber, and

behavioral therapy. Laxatives include hyperosmolar agents such as lactulose and

PEG 3350. Lubricants such as mineral oil and Kondremul® are helpful to

lubricate the intestine for easier passage of stool. These should only be used

in children older than 3 years of age and those without a high risk for

aspiration. Some have advocated the use of fatsoluble vitamin supplementation

when mineral oil products are used, but there is little evidence to suggest

this is truly necessary. Increasing fluid and fiber intake is also critical to

longterm success in treating constipation. Table 13.8 outlines the recommended

daily fiber intake for different ages. Fiber should be increased gradually

toward the goal to minimize side effects of flatulence. Regular toileting should

be encouraged with positive reinforcement in the school-age child. Toilet

training should be discontinued in the training toddler until retentive

behaviors have improved. Education of patients and parents about the

pathophysiology of constipation, the etiology of encopresis when present, and

the expectations of therapy are vital. Close follow-up is a mainstay of

treatment. Successful therapy may take months to years to complete.

Approach to the Patient

with Severe Chronic Constipation

Disimpaction and evacuation of stool in the

patient with severe chronic constipation or one who has failed simple therapy

presents a challenge, particularly in the emergency department setting. A

series of phosphate enemas may not be sufficient to disimpact a larger stool

mass. Use of PEG with electrolytes solution (GoLYTELY®) as a lavage either

orally or via nasogastric tube at a dose of 10 to 25 mL per kg per hour up to

1000 mL per hour until stool is clear may be helpful to treat more severe

impactions. This method should be done in the hospital under supervision of a

physician with close monitoring of the patient’s volume and cardiovascular

status and electrolytes. Risks may be higher in patients with complex medical conditions

such as cardiac disease. Gastrograffin or N-acetylcysteine enemas may be an

additional method of disimpaction, especially in the case of distal intestinal

obstructive syndrome as occurs in patients with cystic fibrosis. In cases of

very severe fecal impaction, surgical disimpaction may be necessary. The use of

milk and molasses enemas in children is falling out of favor in many

institutions as a result of safety concerns following several case reports of

serious adverse events, including one death, after administration. The other components

of constipation therapy apply as already outlined previously and in Table 13.7.

Suggested Readings

Benninga MA, Voskuijl WP, Taminiau JAJM.

Childhood constipation: Is there new light in the tunnel? J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr 2004;39:448–464.

Constipation Guideline Committee of the North

American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition.

Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children:

recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:e1–e13.

Loening-Baucke V. Prevalence, symptoms and

outcome of constipation in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr 2005;146:359–363.

Loening-Baucke V, Krishna R, Pashankar DS.

Polyethylene glycol 3350 without electrolytes for the treatment of functional

constipation in infants and toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr

2004;39:536–539.

Michail S, Gendy E, Preud’Homme D, et al.

Polyethylene glycol for constipation in children younger than eighteen months

old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;39:197–199.

Nurko S, Youssef NN, Sabri M, et al. PEG3350 in

the treatment of childhood constipation: a multicenter, double-blinded,

placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr 2008;153:254–261.

Pashankar D, Loening-Baucke V, Bishop W. Safety

of polyethylene glycol 3350 for the treatment of chronic constipation in

children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:661–664.

Walker M, Warner BW, Brilli RJ, Jacobs BR.

Cardiopulmonary compromise associated with milk and molasses enema use in

children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;36:144–148.

Youssef N, Peters JM, Henderson W, et al. Dose

response of PEG 3350 for the treatment of childhood fecal impaction. J Pediatr

2002;141(3):410–414.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar